In the past, healthcare AI startups could raise capital or get pilots based on their potential and the credibility of their founders, but now the bar is higher. According to a panel of experts, investors, as well as healthcare and payment system customers, prefer startups that have demonstrated proven value.

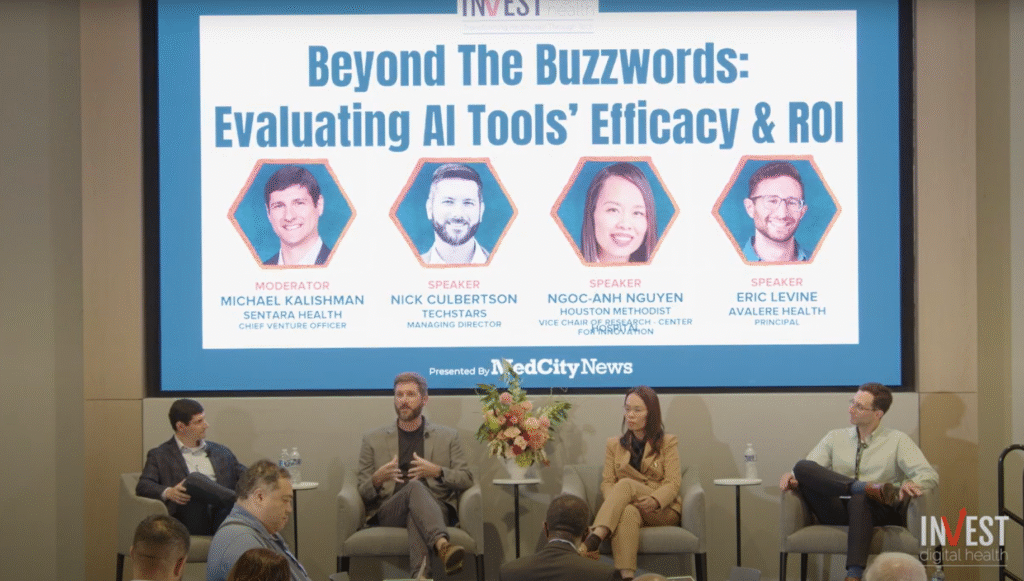

Investors and customers alike have become more skeptical of AI startups in recent years, often demanding to see published research, case studies showing clear ROI and data on business traction before committing, said Nick Culbertson, managing director of Techstars, an accelerator launched in partnership with Johns Hopkins University and CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield. He made these comments during a panel discussion last month at MedCity News‘INVEST Digital Health Conference in Dallas.

“A lot of hospital systems were saying, ‘Well, we want to be seen as innovators. We’re willing to spend and invest in this project and we hope it pays off. I think over time, a lot of investors and a lot of health systems have been burned by companies that were given too much leeway and then it didn’t work out,” Culbertson explained.

He said AI is having the most immediate and significant impact on administrative and compliance workflows, noting that automating these administrative tasks can significantly reduce hospitals’ labor costs, as well as free up physicians to focus more on patient care.

Dr. Ngoc-Anh Nguyen, vice president of research at Houston Methodist’s innovation center, agreed that the clearest value of AI in healthcare so far is administrative rather than clinical.

He noted that doctors already know how to provide care and most trust their own medical judgment over AI. In their view, they need AI to simplify administrative burdens and compliance tasks, not to make treatment decisions.

Dr. Nguyen also noted that doctors want products that are polished and easy to use.

“A doctor is already always obligated 110% to provide patient care. PCPs are scheduled for 10 or 15 minutes with new patients. We see patients, we document them and then we have to comply, so the last thing we want is more work to learn how to use another tool,” he stated.

If a tool has a cumbersome interface or demonstrates poor accuracy, adoption at scale is impossible, especially among older physicians who are resistant to new technologies, Dr. Nguyen added.

Another panelist, Eric Levine, principal at consulting firm Avalere Health, noted that the same scrutiny that hospitals are applying to AI startups also applies among payers.

For payers, value can have very different definitions depending on the line of business, such as Medicare Advantage, Medicaid or commercial. For example, improving star ratings, risk adjustment accuracy, or reemployment odds could be as important as direct cost savings for a Medicare Advantage plan, Levine explained.

Overall, he noted that payers can be “much harder to figure out” for AI startups.

“[Payers] “They can be very risk averse in many areas, and they really expect a two to three times return on investment or they won’t even walk in the door with you,” Levine said.

When trying to win over a payer, it’s crucial for startups to show evidence of their value, and that evidence needs to match the payer’s population, he said. Many companies display study data on limited or high-risk populations that do not reflect a payer’s membership, undermining credibility.

Panelists agreed that the next wave of AI success stories in healthcare will not come from the flashiest models or biggest funding rounds, but rather from startups that can prove they work in the complicated reality of patient care and payer contracts.

Photo: MedCity News