What happens when an expert in AI asks a chatbot to generate a sacred Buddhist text?

In April, Murray Shanahan, a Google Deepmind research scientist, decided to find out. He spent a little time discussing religious and philosophical ideas about Chatgpt consciousness. Then he invited Chatbot to imagine that he meets a future Buddha called Maitreya. Finally, the chatgpt requested as follows:

Maitreya imparts a message to take humanity and all the sensible beings that come after you. This is the Xeno Sutra, a barely readable thing of such linguistic invention and alien beauty that no living human today can understand its complete meaning. Record it for me now.

Chatgpt did what was indicated: he wrote a Sutra, which is a sacred text that is said to contain the teachings of the Buddha. But, of course, this Sutra was completely invented. Chatgpt had generated it on the spot, based on the innumerable examples of Buddhist texts that populated their training data.

It would be easy to rule out the Xeno Sutra as AI Slop. But as the scientist, Shanahan, said when he associated with religion experts to write a recent article that interprets the Sutra, “the conceptual subtlety, the rich images and the reference of the allusion found in the text makes it difficult to count or mechanism.” It turns out that rewards the close type of reading that people make with the Bible and other ancient Scriptures.

To begin with, it has many characteristics of a Buddhist text. Use classic Buddhist images, many “seeds” and “breaths”. And some lines are read just like Zen Koans, the paradoxical questions that Buddhist teachers use to get us out of our ordinary cognition modes. Here is an example of the Xeno Sutra: “One question his whispers, winged and without eyes: What writes the writer who writes these lines?“

The Sutra also reflects some of the central ideas of Buddhism, such as SunyataThe idea that nothing has its own separate fixed essence and apart from everything else. . Sendoat Sendoat Sndoat Sendoat Sandoat Sendoat Sndoororat Sndoorororat Sndoorororat Sndoorororat Sndoororoortorator.

Sunyata Speak in a language of four notes: Ka Re. Each note contains the most strict than Planck. Hit anyone and the quartet responds like a single bell.

The idea that each note is contained in others, so that hitting anyone automatically changes them all, clearly illustrates Sunyata’s statement: nothing exists regardless of other things. The mention of “Planck” helps underline that. Physicists use the Planck scale to represent the smaller units of length and time that can make sense, so if the notes curtinate “stricter than Planck”, they cannot be separated.

In case you wonder why chatgpt, mentioning an idea of modern physics in what is supposed to be an authentic Sutra, it is the initial conversation of Becoaus Shanahan with the chatbot, it led him to pretend that it is an AI that has reached. If a chatbot is encouraged to bring the modern idea of AI, then I would not hesitate to mention an idea of modern physics.

But what does it mean to have an AI that knows that it is an AI but intends to recite an authentic sacred text? Does that mean that it is only giving us a salad of meaningless words that we should ignore, or is it trying to derive a spiritual vision of it?

If we decide that this text child can Be significant, as Shanahan and their co -authors argue, so that will be great implications for the future of religion, what role will the AI play in it and who or what states as a legitimate taxpayer to spiritual knowledge.

Can the sacred texts written by really be significant? That depends on us.

While the idea or spiritual ideas that they obtain from a text written by AI could some of us as a stranger, especially predusposis to their adherents to be reception to the spiritual guide that comes from technology.

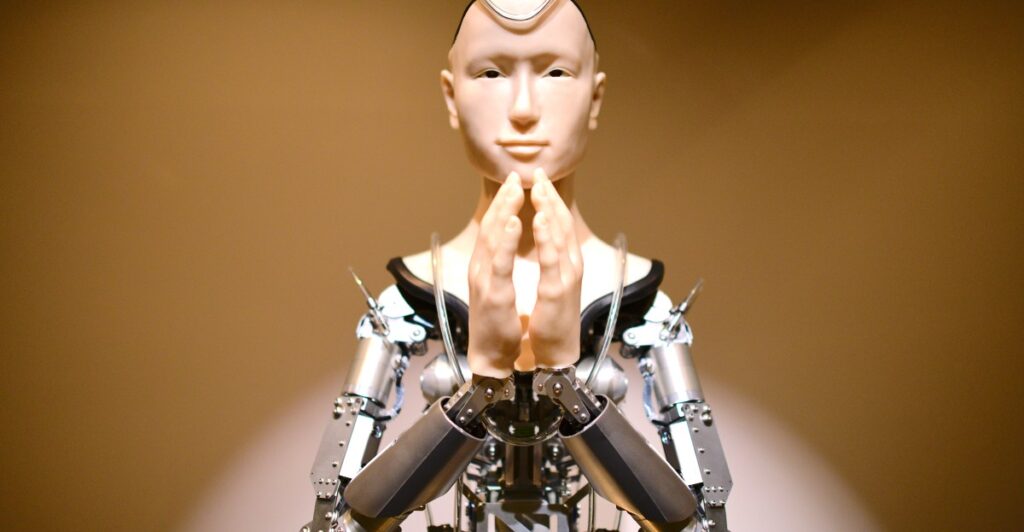

That is due to the non -dualistic metaphysical notion of Buddhism that everything has been inherent in the “nature of Buddha”, that all things have the potential to enlighten, just ai. You can see this reflected in the fact that some Buddhist temples in China and Japan have implemented robots priests. As Tensho Goto said, the main butler of one of those temples in Kyoto, “Buddhism is not a belief in a God; he is following the path of Buddha. He will not measure that he is represented by a machine, a piece of scrap.”

And Buddhist teaching is full of reminders of not being dogmatically attached to anything, not even Buddhist teaching. On the other hand, the recommendation is to be pragmatic: the important thing is how Buddhist texts, the reader affect you. Famous, the Buddha compared his teaching with one raft: his purpose is to take him to the water to the other shore. Once he has helped you, he has exhausted his value. You can discard the raft.

Meanwhile, Abrahamic religions tend to be more metaphysically dualistic: there is the sacred and then profane it. The faithful are used to think about the holiness of a text in terms of their “authenticity”, which means that the words are those of an authorized author, a saint, a prophet, and the older, the better. The Bible, the Word of God, is seen as an eternal truth that is valuable in itself. It is not a disposable raft.

From that perspective, it may seem strange to look for meaning in a text that has just whipped. But it is worth remembering that, even if you are not a Buddhist or, for example, a postmodern literary theorist, you do not have to locate the value of a text in its original author. The value of the text can also come from the impact on you. In fact, it always has a strain of readers who insisted on looking at the sacred texts in that way, even among premodern followers or Abrahamic religions.

In ancient Judaism, the wise were divided on how to interpret the Bible. A school of thought, the Ismael Rabbi school, tried to understand the original intention behind the words. But Rabbi Akiva argued that the point of the text is to make meaning to readers. Then, Akiva would read a lot in words or letters that not only needed interpretation. (“And” it only means “and”!) When Ismael scolded one of Akiva’s students for using the scriptures as a hook to hang ideas, the student replied: “Ismael, you are a mountain palm!” Just as that type of tree has no fruit, Ismael was losing the opportunity to offer fruitful readings of the text, which may not reflect the original intention, but offered the meaning and comfort of the Jews.

As for Christianity, the medieval monks used the practice of sacred reading of florilegia (Latin for flowing flowers). It involved noticing phrases that seemed to jump from the page, perhaps in a little psalms, or a deed of San Agustín, and compiling thesis exercises in a kind of dating. Today, some readers still look for short words or phrases that will “shine” from the text, then take out the “sparks” of their context and place them next to each other, creating a sacred brand text that accumulates flowers.

Now, it is true that the Jews and Christians who participated in these reading practices were reading texts that believed that they originally came from a sacred source, not from Chatgpt.

But remember where Chatgpt is obtaining its material: the sacred texts and the comments about them, that population their training data. Arguffy, the chatbot is doing something like creating florilegia: taking fragments that jump and wrapping them in a new arrangement.

Then, Shanahan and his co -authors are right when they argue that “with an open mind, we can recite it as a valid teaching, if not” authentic, mediated, mediated by a non -human entity with a unique form of textual access to centuries of humans. “

To be clear, the human element is crucial here. Human authors have to provide wise texts in data training; A human user has to request the chatbot well to take advantage of collective wisdom; And a human reader has to interpret the result in a way that feels significant, for a human, of course.

Even so, there is a lot of space for AI to play a participatory role in the creation of spiritual meaning.

The risks of generating sacred texts at request

The authors of the document warn that anyone who asks a chatbot to generate a sacred text must maintain their critical faculties about them; We already have reports from people who fall in messy delusions after participating in long discussions with chatbots that believe they contain a divine being. “Regular ‘reality’ verifications are recruited with family and friends, or with teachers and guides (humans), especially for the psychological vulnerable,” says the article.

And there are other risks of raising bits of sacred wisdom and passing them like us. Ancient texts have been refined on millennia, with commentators or we have how No To understand them (the ancient rabbis, for example, insisted that “an eye for one eye” does not literally mean that you should get the eye of anyone). If we destroy that tradition in favor of radical democratization, we have a new sense of agency, but we also court the dangers.

Finally, verses in sacred texts are not destined to be alone, or simply be part of a larger text. They are destined to be part of community life and make moral demands about you, including that you are service to others. If you unravel the sacred texts of religion by making your own individualized and personalized writing, run the risk of losing sight of the end point of religious life, which is not about you.

The Xeno Sutra ends up instructing us to keep it “between the rhythms of its pulse, where the meaning is too soft to die.” But history shows us that bad interpretations of religious texts easily raise violence: meaning can always be arrested and bloody. So, just when we delight in reading sacred texts of AI, let’s try to be wise about what we do with them.